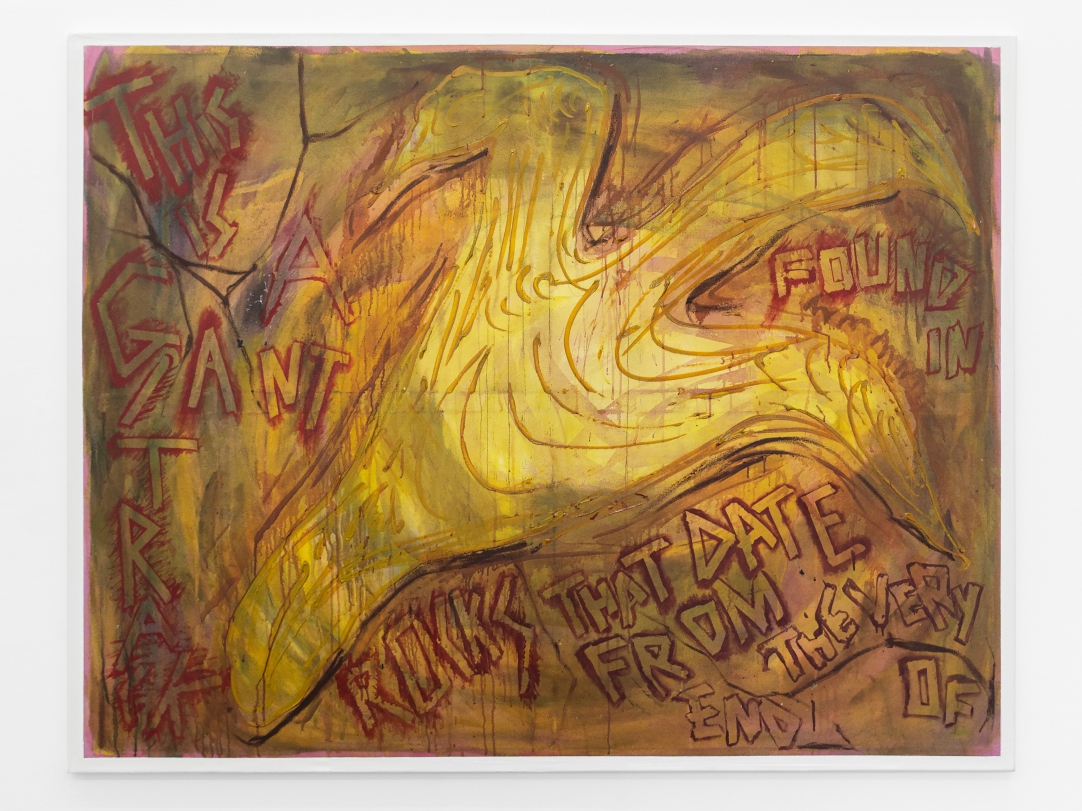

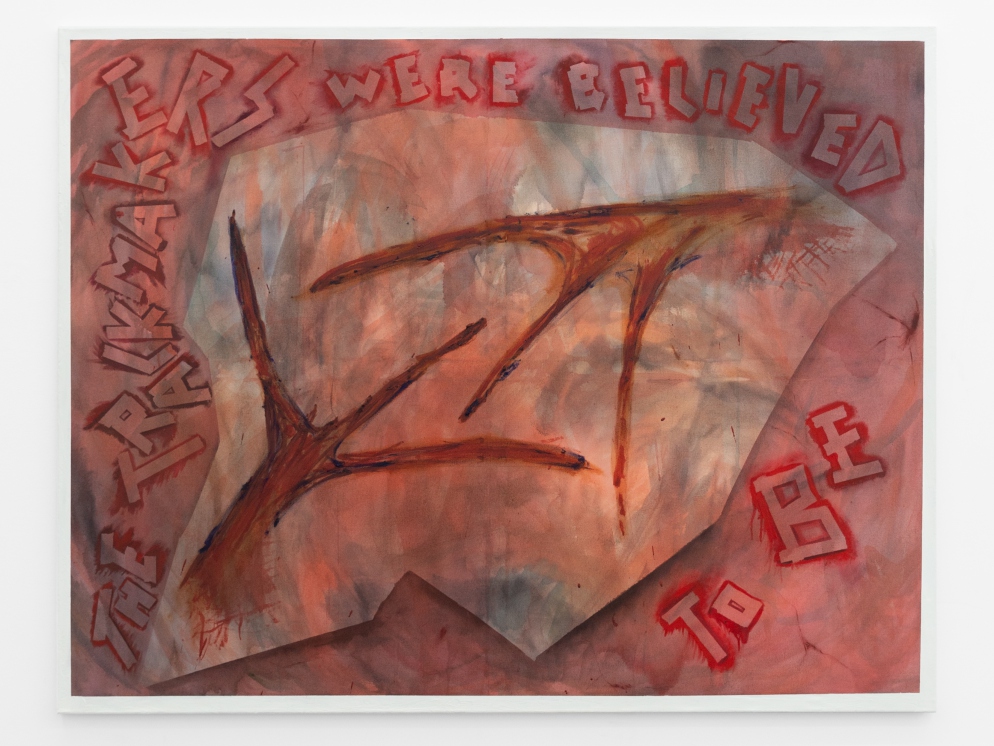

Yana Tsegay understands the cave as a speculative canvas and as an intersection of painting and cultural history in which notions of primordiality are challenged. In her practice the cave is entered speculatively as a place of unlearning and reinvention. Her engagement with cave painting began with the series “Cave Paintings (2017, ongoing)” and continues with the new series “Giant Tracks (2023)” to the present day.

With the white painted frame, as well as with the inscription of a museum descriptive text into the painting, Tsegay makes the museum display format an integral part of the painting. Working with museum exhibition displays and spaces is part of her transformative practice. Here she asks herself: what concepts of culture are inscribed in these spaces? How can the artist create moments of displacement and transform settings? Tsegay aims to reclaim the spaces of museums, palaces, huts, by also working as a performer or with the format of artistic intervention.

In her photo performance “A Natural History Of (2023)” Yana Tsegay moves through the Senckenberg Museum of Natural History in Frankfurt am Main. The leather gloves are an important element with which she visualises herself and becomes aware of her body. The body begins to move differently than usual and interacts, poses and presents itself with the specimens. Through direct eye contact, the viewers are intentionally or unintentionally included in her work, while she plays with moments of self-portrayal as well as objectification in equal measure.

Markus Summerer for Yana Tsegay, Mountains, 2023 (with I. S. Kalter)

Timelines are frequently used in museum exhibitions to clearly present historical events or biographical key dates. They are arranged in a chronological order and claim to provide an objective chronology of what is considered noteworthy. This method of conveying information is always based on a choice that affirms a particular point of view while leaving visible gaps. What lies between the predetermined lines remains hidden, if not completely erased from collective perception.

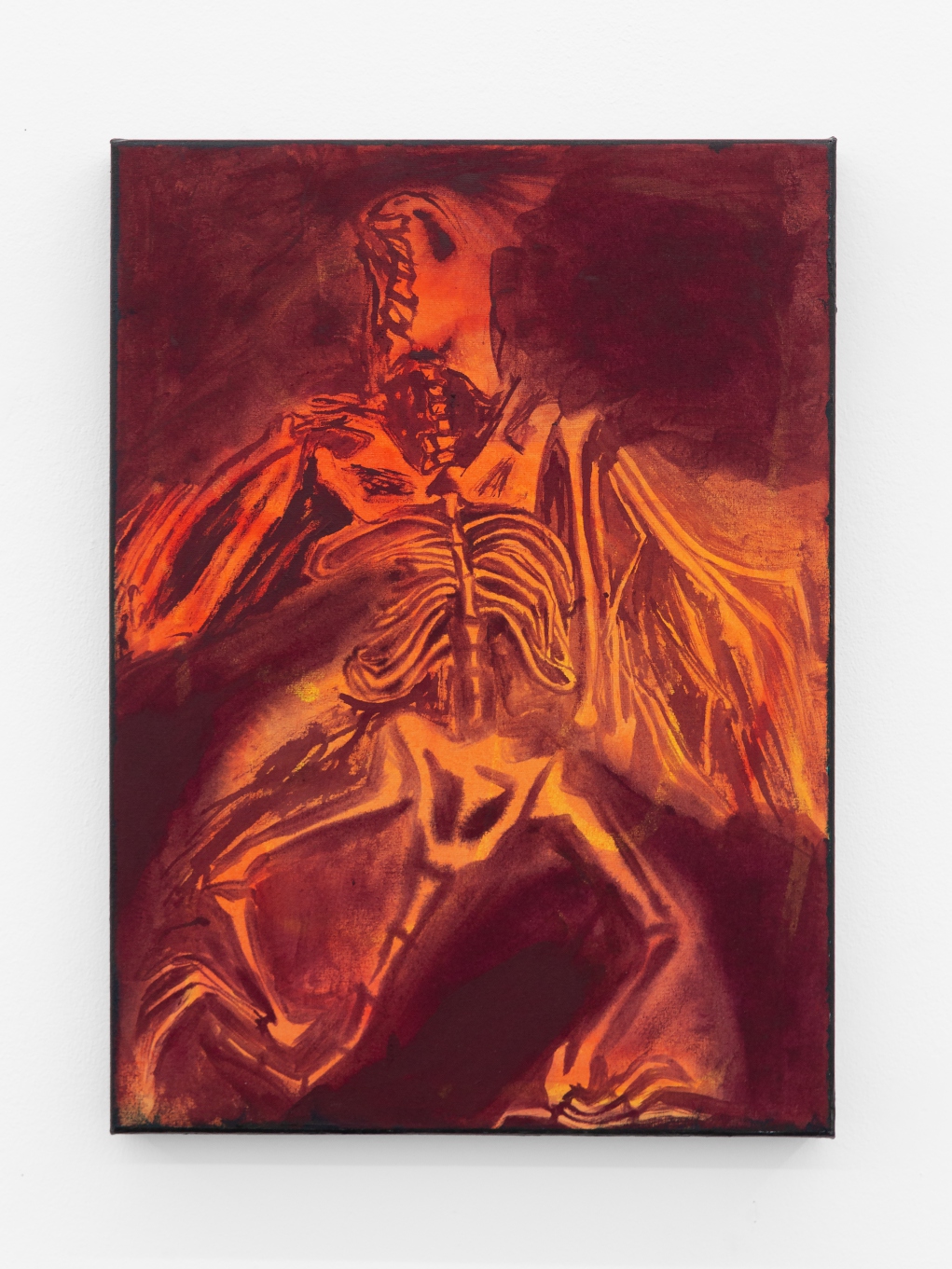

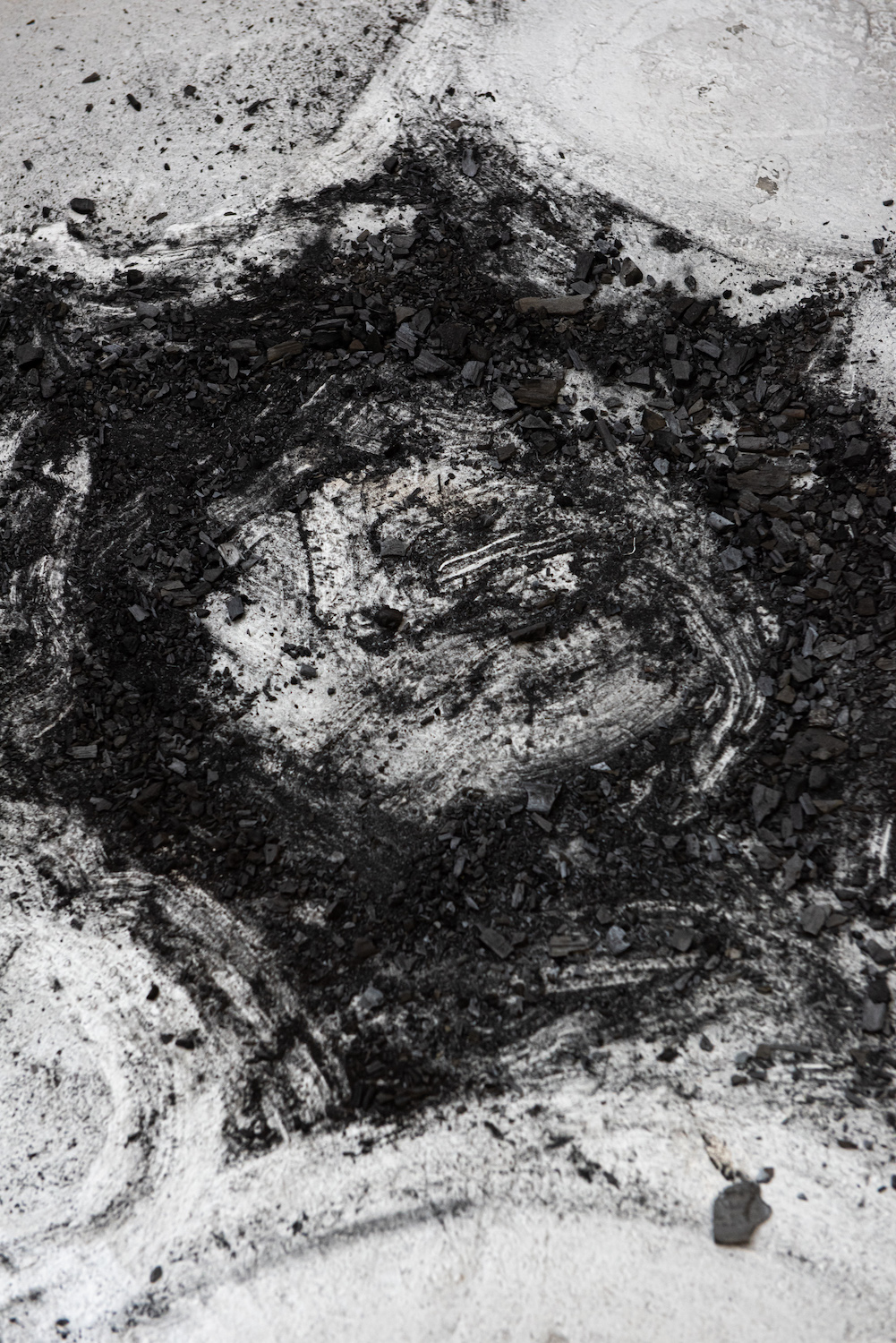

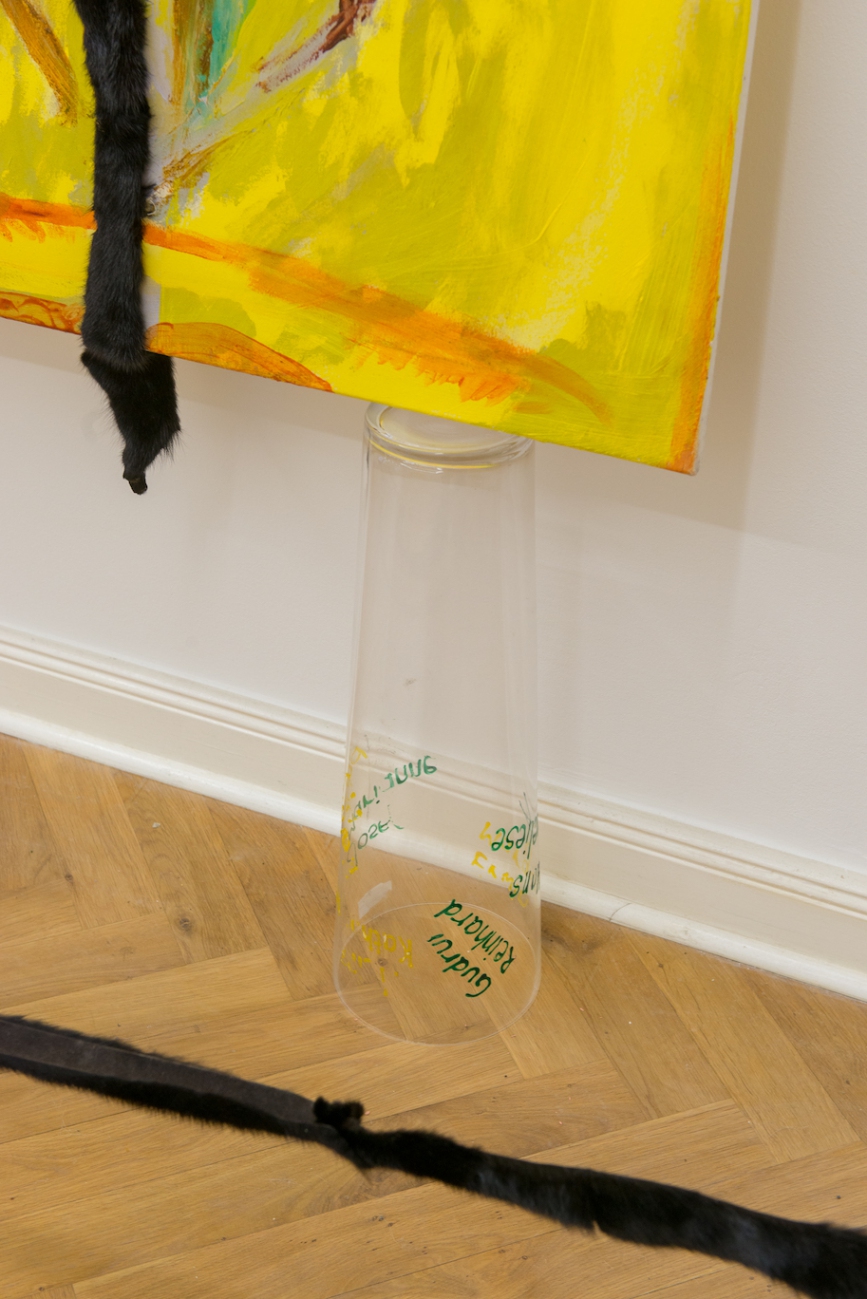

In her solo exhibition The Invention Of Fire, Yana Tsegay appropriates the timeline as a structuring exhibition element. The line stretches across the room, connecting four large-scale canvases on which fire blazes from acrylic and oil sticks. The artist uses traditional painting mediums that she sometimes supplements with scraps of leather and fur. However, Timeline (2022) is made up only of recycled fur glued together. Almost uncomfortably, the still shimmering mink hair makes an appearance, giving the installation a dead liveliness.

Tsegay reaches far back into history to find the fire that was lit for the exhibition. Archaeological evidence suggests that humans started using fire around 1.5 million years ago, though some argue that it was much earlier. As long as the discovery sites are viewed within today's national borders, this scientific dispute is ultimately a matter of cultural dominance. Historiography provides interpretations of the past that assist in reinforcing social order. However, we cannot determine what the relationship of gender roles looked like in prehistoric times, any more than we can determine when, where, and who used and dominated the first fireplace. Without a doubt, the ability to make fire played a critical role in the evolution of humanity, so the development of this cultural technique is remembered as a major milestone.

Yana Tsegay's timeline deviates from its traditional function of retrospective historical construction and questions the concept of chronology. Although her connecting line moves purposefully from one image to another, overcoming architectural obstacles, the furry line appears as a spreading scar. Its spurs sprawl into the ground, where it almost fuses with crushed coal. The combustible intends to direct the audience's path, but in doing so it primarily creates another structure, one that appears to be helpful but draws a border. It is true that fire can burn down barriers and thus be used destructively. It cannot, however, be completely tamed. In a subtle way, Yana Tsegay's fire paintings convey the danger, effectiveness, and fascination that flames exude. The artist's exhibition creates a space for critical reflection on our historiography, definitional sovereignty, and the power structures that lie beneath.

Philipp Lange for The Invention of Fire

basis project space, Frankfurt 2022

Yana Tsegay’s solo show takes its title from the Amber Room, built in 1701 by Andreas Schlüter for the Prussian King Frederick William I in the Berlin City Palace. This magnificent room, which carries the will for representation, donation, spoils of war and robbery, has been relocated several times and considered lost since the end of World War II. In 2003 it was faithfully reproduced in the Catherine Palace in St. Petersburg. Cultural scientists are still trying to trace the myth of the Amber Room.

Yana Tsegay’s floor work Amber Plate (2019) is composed of window frames with flyscreens painted with melted sugar and complemented by objects cast with sugar and resin. The artist’s recurrent materials, including fur, leather, pigments and ceramics, are organic and natural materials which are part of the collection of materials from art history that revolves around the formation of myths. The canvases stand on self-built pedestals and feet and by this they take on the character of objects themselves and become part of the installation. They structure and define the exhibition space, as well as a fur string stretched across the room as a barrier tape. The gestural abstraction of the paintings (Amber Panel I-IV, 2019) seems primordial. The almost archaic composition of the pictures is determined by formlessness with earthy colors and contains borrowings from prehistoric cave painting, which – with the Lascaux Caves – is considered the origin of art. ”Prehistoric” or “primitive” are terms that are used by the supposedly Western world to talk about “the other” and to demonstrate superiority.

Thus, in terms of cultural history, Yana Tsegay spans the arc from that first form of artistic expression to institutionalized and representative so-called cultural treasures such as the Amber Room, which always raise the question of cultural appropriation, expropriation, the appropriation of raw materials, and demonstrations of power. These questions are intensified in Yana Tsegay’s self-referential performances – with the aim of dissolving the privileges and hierarchies of the institutional contexts in which the artist works.

Miriam Bettin for The Amber Room at Mountains, Berlin 2019

Yana Tsegay creates installations that drawon paintings, sculptures or found objects and places them in historical-fictional references to cave paintings or the Amber Room. These references create links to the idea of the origin of art and fan out a spectrum of questions about institution, cultural appropriation and artist identity.

candy, which are melted into abstract sculptures, create an aesthetic that undermines the distinction between fake and real, historically true or fictional. The successful balance between inner openness and shoulder-shrugging questioning of attribu- tions leads to an art that – like amber – is sometimes clear and transparent, sometimes opaque and impenetrable.

Leon Joskowitz / KVTV for Verharzungen The Reference, Frankfurt 2020

In my artistic practice, I speculatively enter the cave as a space for imagination and unlearning. I wonder: How is it possible to shift projections of what is perceived as ’the other’? Therefore, I incorporate artistic research on natural history, historiography and mythologies into my work with installation, performance, painting and text.

Performances by Yana Tsegay were shown at Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt, DE (2020); Mountains, Berlin, DE (2019); Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, DE (2018), fffriedrich, Frankfurt, DE (2017) among others.

Recent exhibitions include Moltkerei Werkstatt, Köln, DE (2023); Mountains, Berlin, DE (2023); Kunstverein Friedberg, Friedberg, DE (2023); Basis Projektraum, Frankfurt, DE (2022); Frankfurter Kunstverein, Frankfurt, DE (2021); Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, DE (2020); Mountains, Berlin, DE (2019); The Reference, Frankfurt, DE (2019); CLB Aufbauhaus, Berlin, DE (2017).

Fotos: Julie Becquart, Fenja Cambeis, MOUNTAINS, Ivan Murzin